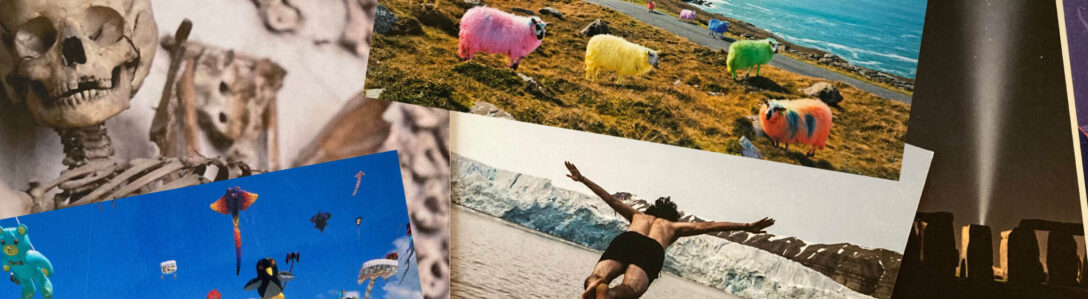

Dexter Morgan, sympathetic serial killer of books and television fame. Fiction shows us the inner workings of characters different from us, possibly increasing empathy.

A message from Editor-in-chief Emily C. Skaftun

To me, summer is for fiction. It’s a habit deeply ingrained by summer reading lists and reading of my own that, without school, I finally had time for. What are days at the beach or pool for, if not reading? Reading for pleasure, which for me means reading fiction.

Later, summer became about not only reading fiction, but also writing it. At some point, I determined that novelist was the answer to the question “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Summer is the season of writing workshops, and I’ve attended my share.

Sometimes I wonder if fiction is really the answer. It feels less “serious” somehow than other types of reading, and there is a stigma, especially about the “genre” fiction that I prefer to read and write.

A study conducted in 2013 seemed to provide some legitimacy, finding that reading “literary” fiction increases theory of mind (according to the Science abstract, ToM, described in write-ups of the study as “empathy,” “is the human capacity to comprehend that other people hold beliefs and desires and that these may differ from one’s own beliefs and desires.”).

Even this study had to get a dig in to “genre (or popular)” fiction, differentiating it from the “literary” fiction that supposedly temporarily improved ToM. Maybe I’m glad that its results were never replicated.

Scientifically provable or not, I believe that reading fiction does increase empathy—and that it matters what fiction we’re reading. Because what is fiction about if not seeing the world through someone else’s eyes? Engaging with their struggles, living with their choices, understanding their motivations—surely, I must believe, this has some impact on how we see non-fictional people. And, I might add, I don’t think science fiction and fantasy is at a disadvantage here. If we can get inside the minds of aliens and elves, humans—even those who are different from us—should be a snap.

As Deena Weisberg, a psychology researcher who tried to replicate the initial ToM findings said, “One brief exposure to fiction won’t have an effect, but perhaps a protracted engagement with fictional stories such that you boost your skills, perhaps that could.” Well, I like to think so.

She’d found that people who could identify more authors scored higher on ToM tests. But even she couldn’t leave well enough alone: “It’s also possible the causality is the other way around: It could be people who are already good at theory of mind read a lot,” she added.

Personally, I need to believe that reading fiction can increase empathy not only to justify my life’s ambitions. I need to believe it because I need to believe that our capacity for empathy can be increased. I need to believe that a world is possible where we don’t rush to assume the worst of people, but instead try to see things from their perspective, where we offer others the grace we need for ourselves.

I need this.

When I fail at something, when I behave not my best, I know the reasons why. I know my intentions. I know what I’m struggling with and I know that I am trying my best to do right in the world. Others, I realize, do not know these things about me. Often, as a result, their assumptions about my behavior are not generous.

What if we all tried to look at each other like interesting, complicated characters in a book? What if we asked ourselves why that road-ragey driver is in such a hurry rather than just honking at them and flipping the bird? I’ll bet we could come up with all kinds of reasons, ranging from minor to life-threatening to absurd. Isn’t that more fun—and more calming—than assuming that person is just a jerk?

No one is just a jerk, not in their own minds. This is one of the things that well-crafted fiction can teach us, with believable villains whose motivation we can understand, if not admire. I’m not saying that no one does bad things for bad reasons—there are certainly those who enjoy hurting others—but most people, I also have to believe, mean well.

If we can extend that grace to the flawed characters of literature, why not to our neighbors?

This article originally appeared in the July 27, 2018, issue of The Norwegian American. To subscribe, visit SUBSCRIBE or call us at (206) 784-4617.